We’re back to our tour of Hopewell Village and Furnace in Pennsylvania, and this is the third installment. If you’re interested, the other two posts are below.

I liked the colors of this wagon that’s housed in the barn, but first I’d like to give you a brief history of this place:

Hopewell Furnace was built in 1771 by Mark Bird, who was already an important figure in the quickly growing iron business in the colonies. When the American Revolution came about in 1775, the furnace turned from casting stove plates to supplying cannon and shot to the Continental Army and Navy.

The Hopewell Plantation was sold at a sheriff’s sale in 1788 after Bird suffered financial setbacks that occurred after the war.

The new owners suffered natural disasters, national recession and in the end, litigation closed the furnace in 1808.

It reopened in 1816 and from then until 1831, Hopewell enjoyed its best years under the leadership of Clement Brooke, the furnace’s resident manager, supplying iron products up and down the East Coast. The furnace went out of blast for the last time in June of 1883 after the steel industry began to flourish.

The property remained a summer home for the descendants of the Brooke family until 1935 when it was sold to the federal government and its 214 acres of historic land was set aside as a national historic site in 1938.

Are you taking notes? I hope so.

After we left the cast house, we headed up towards the barn. At each location, the park service has installed audio background on the building, where you can listen to people describe their position on the plantation, facts about their daily life and even what the weather was like.

We met this handsome rooster who showed us who was boss.

George has never seen chickens before and seemed a little interested.

After leaving the barn, we headed towards the springhouse where I pressed the audio button and listened as a woman described her life. She was in charge of housekeeping in the ironmaster’s house and she and her crew of unmarried girls kept the house shipshape, which was quite a job due to the dust created by the furnace.

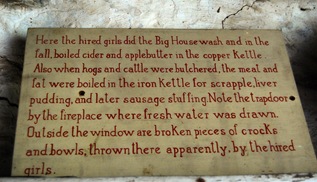

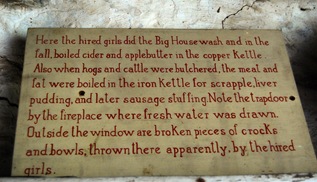

I’m coming up the little set of steps now that leads down into the springhouse. According to the audio and the sign I read, this is where the girls did the wash and in the fall, made cider and apple butter in the kettle on the big stove. The hogs and cattle were also butchered down here, and their meat and fat was boiled for scrapple, liver pudding and sausage.

When I was growing up, scrapple was one of my favorite things to eat at my house. I loved how my mother cooked it, and served with ketchup, it was the best thing about breakfast.

When I grew up however, and found out what exactly was in scrapple, I stopped eating it.

Ok. Where were we? Oh yes, the house.

The ironmaster’s house was built in three stages as the plantation grew. There are a few rooms that are open downstairs, but someone was getting very impatient with me. Someone had already been in the house and out again and was waiting for me to get on with it now.

So I quickly went inside and shot this photo in what looks like the dining room. I think the kitchen is through that door and if I’m not mistaken, that’s a dog bowl on the floor by the door. I’m just saying.

We’re now on the side of the hill and behind us, the NPS has built a visitor’s station. There are also restrooms and much to my husband’s delight, a coffee machine. Tomorrow, if you are still with me, we’ll walk around to the side of the hill where the charcoal was made, and then head back down to the road that will lead us to our path through the woods.

If you’re still with me, that is.

Respectfully submitted,